Introduction

The face is a symbol of a person’s identity as well as an integral component of social communication. Ageing of the face is visible and of significant cosmetic importance so alterations in the facial appearance has been extensively studied. Although facial changes from ageing are specific to each individual as a manifestation of genetics, there is no denying that sooner or later chronological age will begin to show its ravages on the face. The changes occur slowly and are affected significantly by factors, such as ethnicity, health, gender and the lifestyle of the individual.

Gravity is not the sole determinant of the aging face. It has been demonstrated that volume loss, including that of soft tissue and bone, is equally important in the pathogenesis of the stigmata of aging1–2. Facial anatomy is composed of three general elements: skin, soft tissue, and the underlying skeletal support that provides the basic shape of the face. All these elements undergo a spectrum of changes with age resulting in the sad old look.

Facial aging is a dynamic process involving the aging of soft tissue and bony structures. Epidermal thinning and the decrease in collagen cause skin to lose its elasticity. Loss of subcutaneous fat, coupled with gravity and muscle pull, leads to wrinkling and the formation of dynamic lines. The bones of the face undergo contraction and loss of bony volume and projection thus contributing to the aged appearance3–5. This review addresses the different changes in facial anatomy with some reference to variations by ethnicities.

Skin

Chronologically aged skin is thin, dry, relatively flattened, uneven and lax. It shows a general atrophy of the extracellular matrix, which is reflected by a decrease in the number of fibroblasts and reduced levels and impaired organization of collagen and elastin. With age there is reduction in protein synthesis which affects types I and III collagen in the dermis. There is also an increased breakdown of extracellular matrix proteins with age6–7.

Collagen and elastin keep the skin firm and smooth. The body produces collagen more slowly with increasing age and stops producing elastin shortly after puberty. Because of loss of these proteins, gravity starts to affect the shape of the skin by pulling down on it, causing sagging6–7.

It is a well known fact that skin wrinkling increases with age8. Wrinkling appears to be related to alterations and weakening of the upper dermis9. Wrinkles are classified as atrophic, elastotic, expressional and gravitational10, and each type of wrinkle is characterized by distinct microanatomical changes and each develops in specific skin regions.

The dermal layer thins with age due to reduction in collagen production and elasticity wears out due to disarray of elastin fibers. These changes in the scaffolding of the skin cause the skin to wrinkle and sag. Also, sebaceous glands increase in size but produce less sebum, and the number of sweat glands decreases. All of these changes lead to skin dryness11. Drier skin shows more wrinkles and deeper furrows, with wider intervals8.

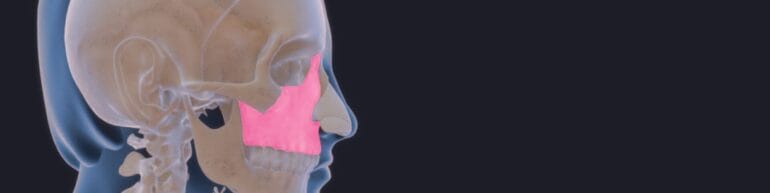

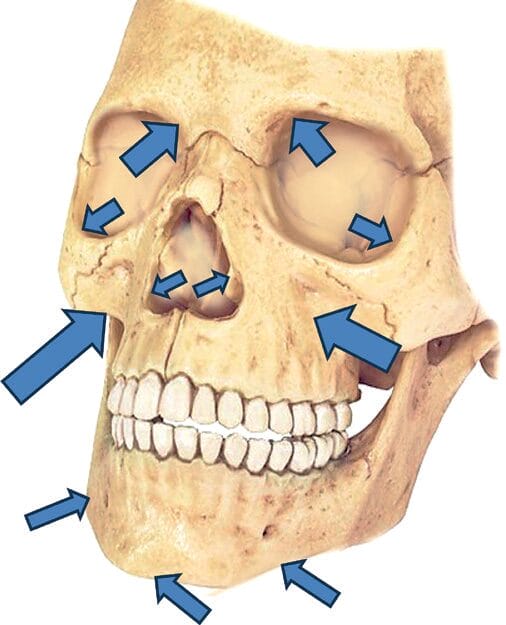

Bony Skeleton

The facial skeleton is generally believed to expand continuously throughout life12–14 while bone resorption in specific areas causes a shift in facial features with age. It is well established that some individuals inherently “age better” than others. These individuals have strong skeletal structure, with youthful bony features that provide good support to the overlying soft tissues15. Bone loss with age weakens the support structure causing the overlying tissue to sag. Bone resorption is primarily involved in the aging of the jawline (maxilla)16–22. The bony skeleton of the head, especially the maxilla, resorbs unevenly with age thereby contributing to the unsymmetrical appearance16–24.

The vertical height of the facial skeleton increases continuously with age unless factors such as tooth loss intervene25. The eye orbital aperture increases with age, in both area and width. Resorption is, however, uneven and site specific16. The bone around the eye recedes with age19 contributing to the signs of periorbital aging such as increased prominence of the under eye fat pad,

elevation of the inner eyebrow, and lengthening of the eyelid24. Bone resorption of the nose results in the appearance of lengthened nose18, 24.

The changes over the lower face include increased prominence of the jowl relative to the area of reduced skeletal support in the prejowl area of the mandible26. The prejowl area of mandible develops into an area of relative concavity due to bone resorption,22 contributing to the appearance of sagging jowls27. Nasolabial fold and groove may be attributed to the loss of projection of the maxilla with aging19, 28. Sagging jowls are an especially noticeable challenge since they make the individual look older by literally changing the shape of the face.

Subcutaneous fat

Subcutaneous fat has been found to be significantly and positively correlated with the sagging intensity in the lower and lateral facial areas. The subcutaneous fat of the face is not stratified as a continuous layer underneath the dermis but is partitioned into discrete anatomic compartments. Uneven absorption of fat contours the face29 and accumulation of subcutaneous fat in certain areas, i.e., heavy nasolabial folds, prominent jowl formation, and accumulation of fat under the chin, also contribute to the appearance of ageing.

Additionally, fat cells in the subcutaneous layer get smaller with age. This leads to more noticeable wrinkles and sagging, since the fat cells are unable to provide padding to hide the damage from the other layers11.

Muscle

Fascia a form of connective tissue provides a sliding and gliding environment for muscles; to suspend organs in their proper place and to transmit movement from muscle to the bones. The superficial and deep facia of the face weakens and loses integrity due to gravity, adding to the cause of facial sagging30. These septa form an interconnecting framework that limits shearing forces on the face31.

The muscles of facial expression decrease in size and become thinner with age, similar to the atrophy of skeletal muscles32.

Repetitive muscle contraction and muscle tone changes with time and contributes to the appearance of superficial and deep dynamic wrinkles during animation33. Although muscles may weaken with age, their relative pull is greater on the less resistant tissues and dermis. This can result in a change of expression. The muscle around the mouth could inundate the perioral skin, resulting in puckered lips in the youthful face but resembling tense, pursed lips with aging.

Signs of facial Ageing

Jawline: Width of the face by the mouth includes the jowls which represent the typical stigmata of aging. Studies have reported that Caucasian females show a higher susceptibility to sagging in the sub zygomatic area (upper side of the chin) as compared to Japanese women residing in Tokyo34–35. Farkas et al (2005)35 observed that Asians had the widest lower facial widths and the African American/Zulu group had the narrowest.

Philtrum is the area between subnasale to lip. A significant increase in the size of the philtrum has been observed with age across all ethnicities36–39.

Length of the face from glabella to chin has been reported to increase with age. Literature indicates that older Japanese have much longer faces than the Caucasians. Farkas et al (2005)35 observed that Asians had the longest and the African American/Zulu group had the shortest facial length from glabella to chin.

Eye area

The eyebrows and eyebrow fat pads are particularly vulnerable to age-related changes. Although overall eyebrow volume does not change with age, the fat volume increases and the soft tissue volume decreases40 giving the look of droopy eyes.

Orbital height, and the height-to-width ratio also increases significantly as a function of age thus showing larger eye socket area41. It has been reported that Caucasians exhibit much more close-set eyes than Asians and Africans. The eye distance increases significantly with age for all ethnicities35.

Eye width increases by about 10% between the ages of 12 and 25 and shortens by almost the same amount between middle age and old age nevertheless, aging does not affect the position of the eyeball proper42. In studies by Farkas et al [2005]35, the Caucasians had the widest eyes while the Asians had the narrowest.

Eye height of Chinese is reported to be shortest and reduces even further with age. The height of the eyes of the Japanese, Caucasians and Africans also reduces significantly with age. In a study by Van den Bosch [1999]42 the distance between the pupil center and the upper eyelid margin showed a small but not significant downward shift with age42.

The levator palpebrae superioris muscle lifts the eyelid upward to open the eye. In the Caucasians this muscle is attached to the skin about 8 to 12 millimeters above the eyelashes so that when the muscle pulls on the skin to open the eye, a fold or line is created. This fold is visible about 10 millimeters above the eyelashes when the eye is open in most women. In the Asian eyelid this muscle attaches very weakly or not at all to the skin but does attach to the tarsus (lower edge of the eyelid) which allows the eye to be pulled up and opened. Because the muscle is not attached to the eyelid skin when the muscle pulls up, the eyelid crease does not appear42. Drooping of the upper eyelid is associated with increased severity of transient and fixed wrinkling at the forehead43. The fat distribution in the upper Asian eyelid is also different in that the fat is present across the entire upper eyelid and not limited to two deep pockets as it is in the Caucasian eyelid. This makes the Asian eyelid look fuller4.

Aging causes a downward shift of the lower eyelid suggesting that aging causes lower eyelid laxity42 .

Lip area

It is a common observation that women who look young for their age have large lips39 and that lip thickness goes down with age36. According to Penna et al, [2009]37 the aged look is due to a loss of elasticity and resultant drooping of the upper lip rather than total volume loss.

Studies by Iblher et al, [2012]38, involving histomorphometric analysis of the lips of young (< 40 years, n = 10) and old (> 80 years, n = 10), revealed statistically significant thinning of the skin (epidermis+dermis) and degeneration of elastic and collagen fibers. The lip (orbicularis oris) muscle becomes thin and lax36, 38.

Nose area

Like other organs, the nose changes as the body ages. The appearance of the nose, as measured by the nasolabial angle and the height/length ratio, has been found to change with age44. With age the nose lengthens and the tip droops, with the columella (the column between the nostrils) and the lateral crurae (outer lining of the nostrils) pushing back45. Changes in the bony foundation that supports the nose in youth, are responsible for many of the soft tissue changes seen in the nose with aging.

As the nasal bones recede the piriform aperture enlarges with aging18. Bone loss is not uniform with preferential bone loss in the lower part of the aperture17, 20, 23, 27. Bone loss here contributes to deepening of the nasolabial fold with age46. The loss of bone in the pyriform area weakens the support of the lateral crura. The anterior nasal spine also recedes with aging (although at a slower rate), and this reduced skeletal support contributes to retraction of the columella, with downward tip rotation and apparent lengthening of the nose with aging26.

Nasal volume, area, and linear distances have been reported to increase from childhood to old age, while the nasal tip angle decreases as a function of age47. Nasolabial fold severity increases with decreasing dermal elasticity48. In a study conducted by Farkas et al, [2005]25 Caucasians and Asians exhibited longer noses than the African American/Zulu group and Asians and African American/Zulu group appeared to exhibit wider noses than the Caucasians.

Summary

With ageing comes wisdom, experience, and accomplishments as well as the signs of facial ageing that is the topic of intense scrutiny in the cosmetic industry. The skin gets dry with loss of collagen and rearranged elastin. The underlying layer of fat shrinks so that the face no longer has a plump, smooth appearance. Then there are the unavoidable wrinkles that can be accelerated with sun exposure and cigarette smoking. The deep wrinkles in the forehead and between the eyebrows are called expression, or animation, lines. They’re the result of facial muscles continually tugging on, and eventually creasing, the skin. Uneven skin tone and age spots appear with age and are exacerbated with sun exposure.

Subcutaneous fat is evenly distributed in the young, with some pockets here and there that plump up the forehead, temples, cheeks, and areas around the eyes and mouth. With age, that fat loses volume, clumps up, and shifts downward resulting in sagging and bulging in different areas of the face.

It is a combination of skin changes, bone desorption, loss of muscle tone subcutaneous fat distribution and greying hair that imparts the look of aging of the face. Ageing of the face is visible and of significant cosmetic importance so alterations in the facial appearance with age has been extensively studied in an attempt to perhaps slow down the process or to repair the damage in the plastic surgery and cosmetic industries.

References

- Donath AS, Glasgold RA, Glasgold MJ. Volume loss versus gravity: new concepts in facial aging. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007, 15(4):238-243.

- Levine RA, Garza JR, Wang PT, Hurst CL, Dev VR. Adult facial growth: applications to aesthetic surgery. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2003, 27(4):265-268.

- Kahn DM, Shaw RB. Overview of current thoughts on facial volume and aging. Facial Plast Surg. 2010, 26(5):350-355.

- Terino EO, Edwards MC. Alloplastic contouring for suborbital, maxillary, zygomatic deficiencies. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2008, 16:33–67.

- Whitaker LA, Bartlett SP. Skeletal alterations as a basis for facial rejuvenation. Clin Plast Surg. 1991, 18:197–203.

- Brenneisen, P, Sies, H. and Scharfetter-Kochanek, K. Ultraviolet B irradiation and matrix metalloproteinases: from induction via signaling to initial events. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2002, 973:31–43.

- Fischer GJ, Wang ZQ, Data SC et al. Pathophysiology of premature skin aging induced by ultraviolet light. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997, 337:1419–1428.

- Choi JW, Kwon SH, Huh CH, Park KC, Youn SW. The influences of skin visco-elasticity, hydration level and aging on the formation of wrinkles: a comprehensive and objective approach. Skin Res Technol. 2012 19(1): e349-e355.

- Batisse D, Bazin R, Baldeweck T, Querleux B, Lévêque JL. Influence of age on the wrinkling capacities of skin. Skin Res Technol. 2002. 8(3):148-154.

- Glogau RG. Aesthetic and anatomical analysis of the aging skin. Semin. Cutan. Med. Surg. 1996, 15, 134–138.

- Brannon H. What Causes Wrinkles. Effects of Sunlight, Free Radicals, Hormones, Muscle Use, and Gravity, 2007, http://dermatology.about.com/cs/beauty/a/wrinklecause.htm

- Hellman M. Changes in the human face brought about by development. Int J Orthod. 1927, 13:475.

- Lasker GW. The age factor in bodily measurements of adult male and female Mexicans. Hum Biol. 1953, 25:50.

- Bartlett SP, Grossman R, Whitaker LA. Age-related changes of the craniofacial skeleton: an anthropometric and histologic analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992, 90:592–600.

- Louarn C, Buthiau D, Buis J. Structural aging: the facial recurve concept. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2007, 31:213–218.

- Kahn DM, Shaw RB, Jr Aging of the bony orbit: a three-dimensional computed tomographic study. Aesthet Surg J. 2008, 28:258–264.

- Pessa JE, Chen Y. Curve analysis of the aging orbital aperture. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002, 109:751–755.

- Shaw RB, Jr, Kahn DM. Aging of the midface bony elements: a three-dimensional computed tomographic study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007, 119:675–681.

- Mendelson BC, Hartley W, Scott M, McNab A, Granzow JW. Age-related changes of the orbit and midcheek and the implications for facial rejuvenation. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2007, 31:419–423.

- Pessa JE, Zadoo VP, Yuan C, Ayedelotte JD, Cuellar FJ, Cochran CS, Mutimer KL, Garza JR. Concertina effect and facial aging: nonlinear aspects of youthfulness and skeletal remodeling, and why, perhaps, infants have jowls. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999[b], 103:635–644.

- Pessa JE. An algorithm of facial aging: verification of Lambros’s theory by three-dimensional stereolithography, with reference to the pathogenesis of midfacial aging, scleral show, and the lateral suborbital trough deformity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000, 106:479–488.

- Pessa JE, Slice DE, Hanz KR, Broadbent TH, Jr, Rohrich RJ. Aging and the shape of the mandible. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008, 121:196–200.

- Pessa JE, Zadoo VP, Mutimer KL, Haffner C, Yuan C, DeWitt AI, Garza JR. Relative maxillary retrusion as a natural consequence of aging: combining skeletal and soft tissue changes into an integrated model of midfacial aging. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998, 102:205–212.

- Mendelson B, Wong CH. Changes in the facial skeleton with aging: implications and clinical applications in facial rejuvenation. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2012, 36(4):753-760.

- Rosas A, Bastir M. Thin plate spline analysis of allometry and sexual dimorphism in the human craniofacial complex. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2002, 117:236.

- Pecora NG, Baccetti T, McNamara JA., Jr The aging craniofacial complex: a longitudinal cephalometric study from late adolescence to late adulthood. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2006, 134:496–505.

- Pessa JE, Peterson ML, Thompson JW, Cohran CS, Garza JR. Pyriform augmentation as an ancillary procedure in facial rejuvenation surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999[a], 103:683–686.

- Shaw RB, Jr, Katzel EB, Koltz PF, Kahn DM, Girotto JA, Langstein HN. Aging of the mandible and its aesthetic implications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010, 125:332–342.

- Rohrich, Rod J, Pessa, Joel E. The Fat Compartments of the Face: Anatomy and Clinical Implications for Cosmetic Surgery. Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery. June 2007, 119(7):2219-2227.30 Khazanchi R, Aggarwal1 A, Johar M. Anatomy of aging face. Indian Journal of Plastic Surgery 2007, 40(2):223-229.

- Rohrich RJ, Pessa JE. The Retaining System of the Face: Histologic Evaluation of the Septal Boundaries of the Subcutaneous Fat Compartments Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery: 2008, 121(5):1804-1809.

- Le Louarn C, Buthiau D, Buis J. Structural aging: the facial recurve concept. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2007, 31(3): 213-218.

- Farkas JP, Pessa JE, Hubbard B, Rohrich RJ. The science and theory behind facial aging. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2013, 1(1):e8-e15.

- Tsukahara K, Fujimura T, Yoshida Y, Kitahara T, Hotta M, Moriwaki S, Witt PS, Simion FA, Takema Y. Comparison of age-related changes in wrinkling and sagging of the skin in Caucasian females and in Japanese females. J Cosmet Sci. 2004, 55(4):351-371.

- Farkas, Leslie G Katic, M; Forrest, C. International Anthropometric Study of Facial Morphology in Various Ethnic Groups/Races. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery 2005, 16(4):615-646.

- Sforza C, Ferrario VF. Three-dimensional analysis of facial morphology: growth, development and aging of the orolabial region. Ital J Anat Embryol. 2010, 115(1-2):141-145.

- Penna V, Stark GB, Eisenhardt SU, Bannasch H, Iblher N. The aging lip: a comparative histological analysis of age-related changes in the upper lip complex. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009, 124(2):624-628.

- Iblher N, Stark GB, Penna V. The aging perioral region — do we really know what is happening. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012, 16(6):581-585.

- Gunn DA, Rexbye H, Griffiths CE, Murray PG, Fereday A, Catt SD, Tomlin CC, Strongitharm BH, Perrett DI, Catt M, Mayes AE, Messenger AG, Green MR, van der Ouderaa F, Vaupel JW, Christensen K. Why some women look young for their age. PLoS One. 2009, 1;4(12):e8021.

- Papageorgiou KI, Mancini R, Garneau HC, Chang SH, Jarullazada I, King A, Forster-Perlini E, Hwang C, Douglas R, Goldberg RA. A three-dimensional construct of the aging eyebrow: the illusion of volume loss. Aesthet Surg J. 2012, 1;32(1):46-57.

- Sforza, Gaia Grandi, Francesca Catti, Davide G. Tommasi, Alessandro Ugolini, Virgilio F. Ferrario Age- and sex-related changes in the soft tissues of the orbital region Forensic Science International 2009, 185(1–3):115.e1-115.e8.

- Van den Bosch WA, Leenders I, Mulder P. Topographic anatomy of the eyelids, and the effects of sex and age. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999, 83(3):347-352.

- Ezure T, Amano S. The severity of wrinkling at the forehead is related to the degree of ptosis of the upper eyelid. Skin Res Technol. 2010, 16(2):202-209.

- Edelstein DR. Aging of the normal adult nose. Laryngoscope. 1996, 106:1–25.

- Rohrich RJ, Hollier LH, Jr, Janis JE, Kim J. Rhinoplasty with advancing age. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004, 114:1936–1944.

- Barton FE, Gyimesi I. Anatomy of the nasolabial fold. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997, 100:1276–1280.

- Sforza C, Grandi G, De Menezes M, Tartaglia GM, Ferrario VF. Age- and sex-related changes in the normal human external nose. Forensic Sci Int. 2011, 204(1-3):205.e1-9.

- Ezure T, Amano S. Involvement of upper cheek sagging in nasolabial fold formation. Skin Res Technol. 2012, 18(3):259-264.